How to Estimate Project: Time, Cost and Resources. Techniques & Types for Accurate Planning

How to Describe Goals and Deadlines in a Project Charter

Creating a project charter is a foundational step in project management. This document, usually concise at 3–5 pages regardless of project size, sets the stage for what lies ahead. Here's a breakdown of what a project charter includes and how to effectively articulate goals and timelines within it.

The Title of a Project Charter

A project charter begins with a title. This might seem trivial, but it's anything but. The title should be informative and easily understandable because it's something you'll live with for the duration of the project. It has to resonate with you and the project's essence.

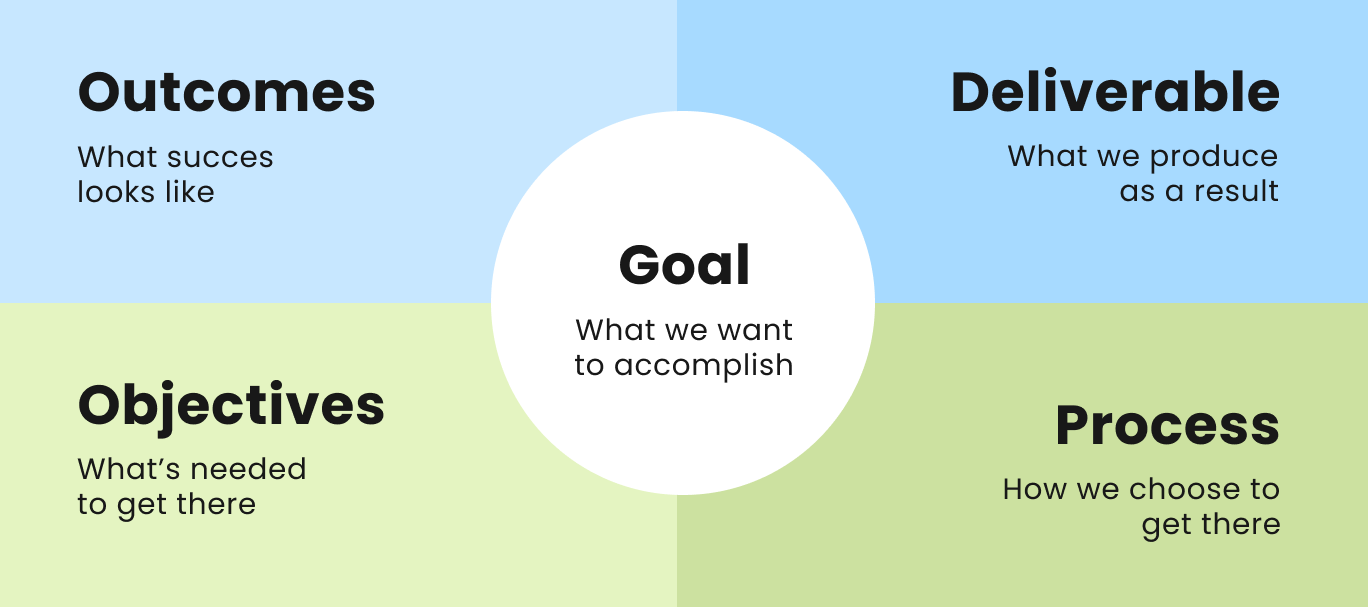

Defining Project Goals

Goals are what you aim to achieve beyond the mere activities of the project. For instance, stating the goal of an IT system implementation as “to create and implement an information system” is redundant. It's like digging a hole to have a hole.

Goals should serve a purpose beyond the activity itself.

How do we measure success? Is the system efficient, effective, and does it meet the needs it was designed to address? Ensure that your project goal isn't just a restatement of the project activity.

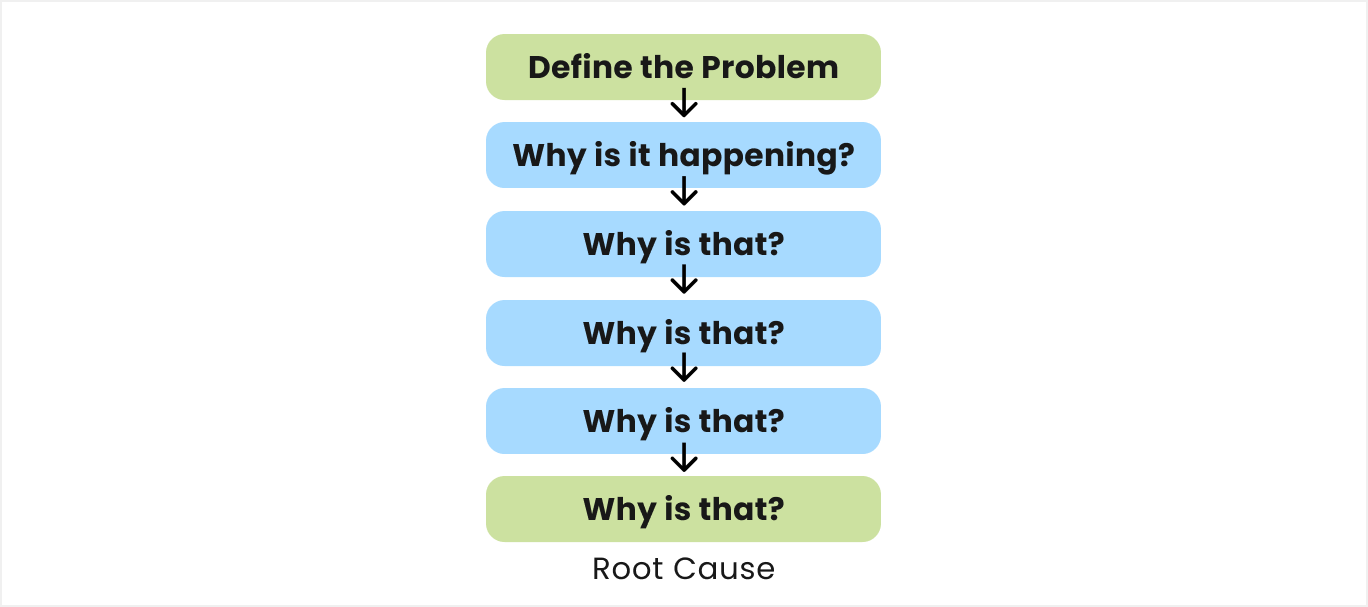

The “5 Whys” Rule

The next point is about verifying the goal. Once a goal is formulated, there is the "5 Whys" rule.

Start with the initial requirement, then ask "Why?" five times to drill down to the core reason for the project. This iterative questioning can help ensure that the goal is well-considered.

For example, the client says: “We need to implement an electronic document management system”. What we have to next is to ask why. Then, you can get the answer: “It will speed up the document flow within the company”. Keep going asking why until you reach the fifth answer. That’s how it works. This rule helps distinguish genuine goals from superficial ones.

But there is an exception:

If any of the "Whys" ends with "money," you've reached a fundamental objective and can stop there.

This rule helps distinguish genuine goals from superficial ones.

Setting the Framework with Deadlines

The most critical aspect of a project charter is establishing boundaries. By signing the charter, you and the sponsor agree on certain parameters, then the sponsor steps back to await results. When defining these parameters, consider what you've committed to and ensure it includes realistic deadlines.

Remember, that the charter outlines major milestones rather than a detailed schedule. Include only the most critical, project-defining deadlines to avoid cluttering your charter with unnecessary milestones.

In simple projects, there may be just one milestone. But there can be more in more complicated projects, which is especially common for the construction industry or manufacturing.

Estimating Timelines

The most common question when making a charter is how to assess timelines at this stage. Often, project initiation provides a rough timeline. At this stage, involving team experts is crucial for a realistic assessment.

The initiation phase itself usually lasts very short, maybe 2–3 days, sometimes even hours. That's why here we have quick expert assessments. We simply won't have time to create a schedule.

Why is that? Because initiation is a stage where no one is responsible for anything yet. The company is still not sure if it can take the project. So, it might end up leading to nothing. Hence, we cannot afford to spend many resources on assessment. It's too costly for us.

In industries where capital expenses are high (those that cannot be recouped), such as construction, manufacturing, film industry — initiation lasts longer and consists of several stages. And by initiation, there is already quite detailed assessment because the risks in these industries are colossal. Sometimes there's a concept of a pre-project — a project that aims to gather requirements, schedules, and plans for a future big project.

In IT projects, capital expenses are not significant; they are proportional to programmers' salaries. There's nothing like spending huge amounts at the beginning, and everything is only useful if we reach the end. It's more advantageous to start working faster than to think for a long time.

The Role of Knowledge Base

Expert judgments form the basis of early-stage estimates, reflecting the team's subjective opinions and experiences. But also, there is one more thing that you can rely on when making estimations — a knowledge base.

It's crucially important. But unfortunately, it often doesn't work, becomes cluttered, or remains unused. But even if you're unlucky with the corporate knowledge base, nothing prevents you from creating your personal knowledge base, where you will reflect personal life experience, deposit successful project charters, risk registers.

All these artifacts are tremendously reusable. For example, in the risk register, up to 90% can be reused if it's the same company or a similar customer. 70-80% of hierarchical structures can also be reused.

Understanding the Margin of Error

It's essential to understand that estimates at the initiation stage are rough estimates.

According to PMI statistics, the error margin of such estimates is about 50%.

It's good accuracy for the initiation stage. Later, you will make a more accurate plan, where accuracy is about 25%. And as the project progresses, the accuracy increases.

To manage this uncertainty, project charters often include a contingency of plus 50% to the initial estimates when negotiating with sponsors.

Conclusion

The project charter is more than just an administrative step; it's a blueprint for success. It defines the project's goals, sets realistic expectations with sponsors, and lays the groundwork for effective project management.

By clearly articulating goals, applying the "5 Whys" technique, and judiciously setting deadlines, you can ensure that your project charter is both a guiding light and a practical tool for your project's journey.