Phases of Project Life Cycle: 5 Key Phases Explained

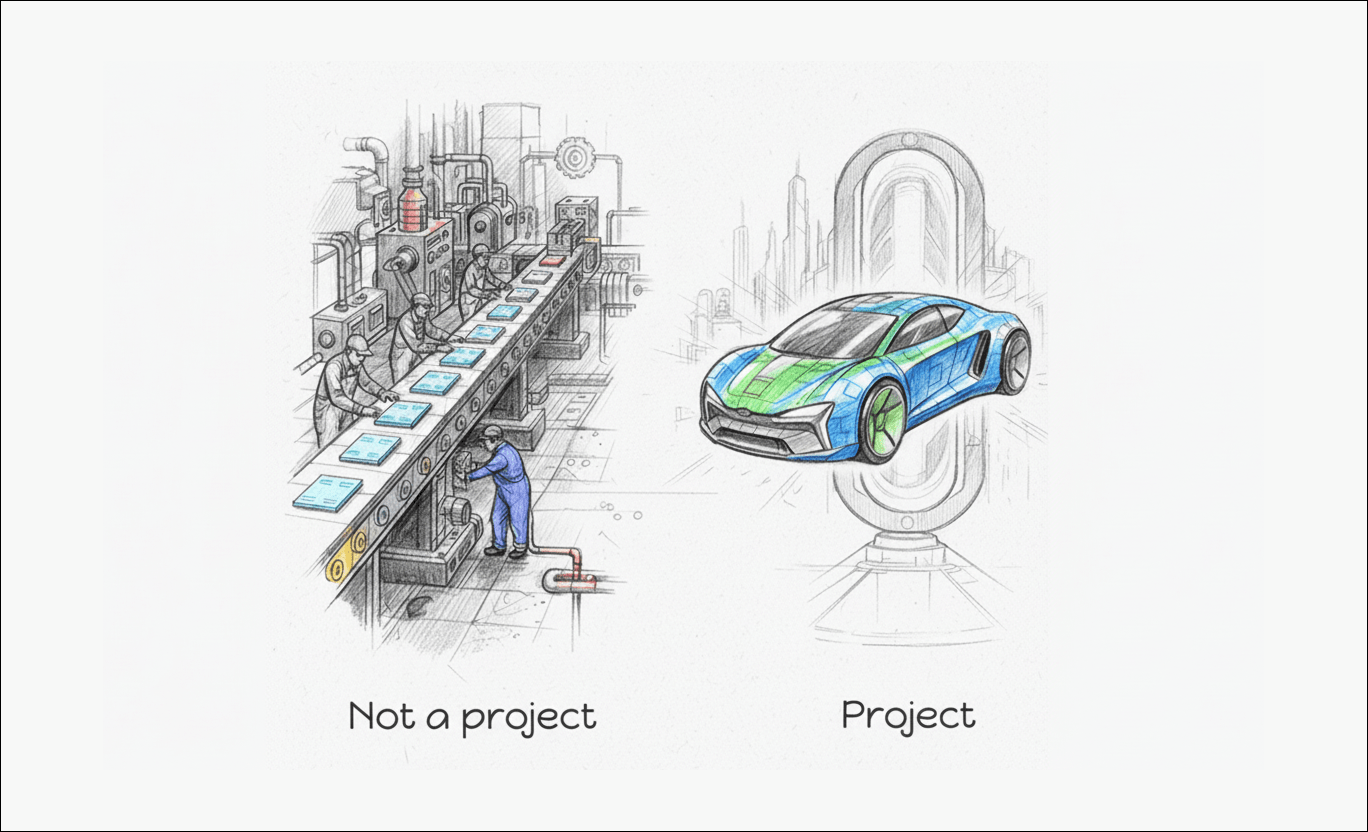

What Is a Project and What Is Not? Understanding the Difference

What exactly is a project, and what is not? Imagine your boss says: "Here's a project. Do it". Your first task as a manager? Step back and ask yourself: "Is this really a project? Or is it just something labeled as one by management?"

Defining a project and project characteristics

According to the PMBOK (Project Management Body of Knowledge), a project is described as a temporary endeavor undertaken to create unique products, services, or results within defined constraints, such as time, budget, and resources. However, this definition doesn’t always make it easy to separate a project from non-project activities.

In practice, a project is characterized not only by time constraints and resource availability but also by a high degree of uncertainty. Unlike ongoing operations, projects have a defined beginning and end, a clear objective, and produce unique results.

Project management vs. product management

But what if there's high uncertainty but no definite end? In such cases, project management approaches can still be used, but they typically become inefficient. It's better to apply product management approaches like Scrum.

If project management is about accomplishing something complex within constraints, then product management is when there are no critical constraints but high uncertainty.

For example, we're developing Google Maps. In Google's case, budget constraints are likely less critical, especially compared to contracting with a customer or being a significantly smaller company. Is it important for Google to meet deadlines? Probably not, as a few months' delays are also not critical. What's significant is making the product perfect, ensuring people like it, and avoiding user churn. There's no pronounced end, but uncertainty exists, and we're fully focused on the content, making product approaches more logical.

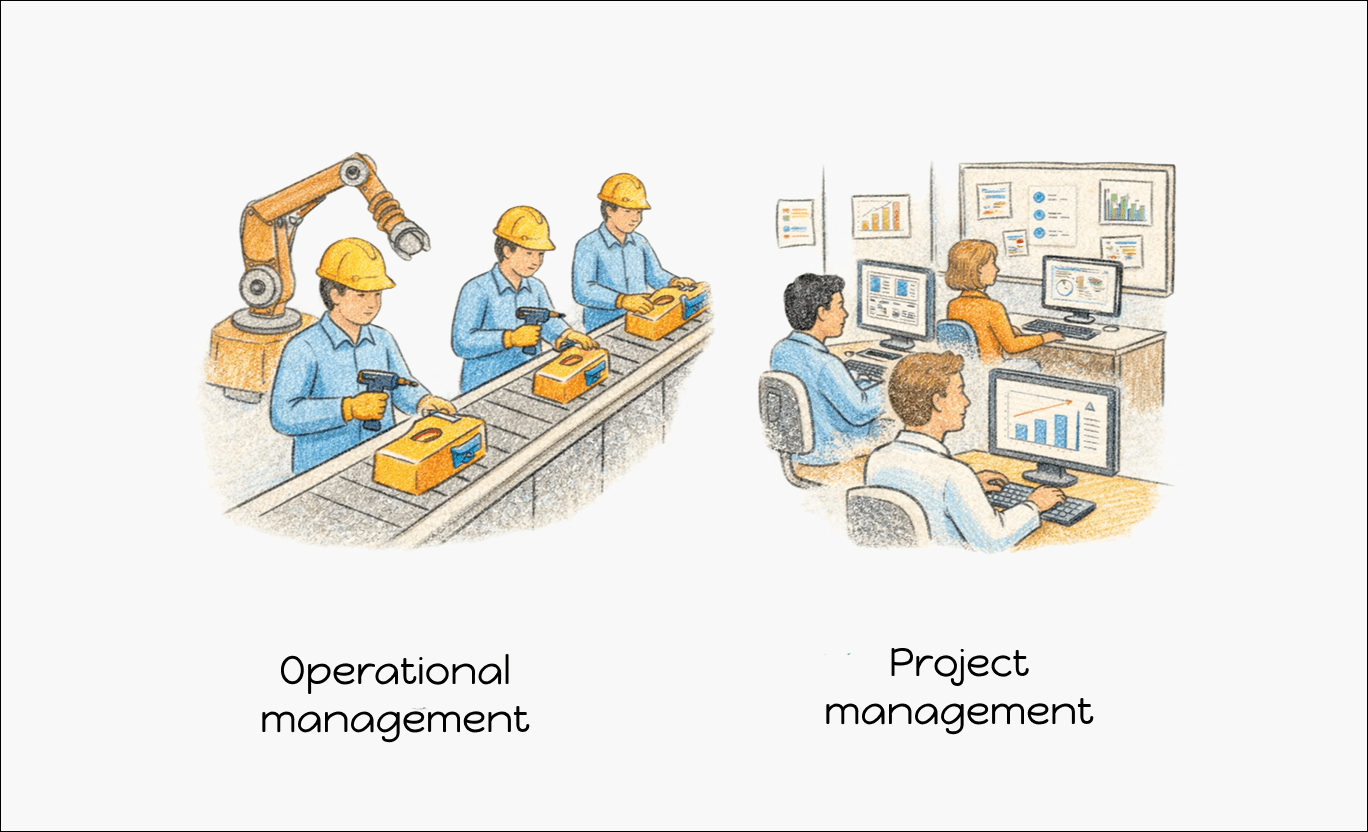

Project management vs. operations management

Another case, which is actually the antithesis of project management, is operations management, like the assembly line in car manufacturing. This is not a project at all. There's no time constraint, no high uncertainty, and tasks repeat day after day. Activities can be broken down into simple, understandable instructions. These enterprises are easy to manage, and operational managers are not needed in large numbers; even one person can manage 500–700 people. While in IT, a team might consist of 10 — max 20 people.

However, if an enterprise begins to expand or introduces new products, elements of project activity emerge, as specific time and resource constraints appear, and tasks become unique, requiring project management.

Conclusion

Thus, the key to understanding project meaning lies in the combination of definitive ends and high uncertainty. If a task has clear time constraints and is associated with unknowns that make its completion complex and unpredictable, it's most likely a project and project management approaches should be applied. Otherwise, if a task is regular and predictable, or does not have a clear time constraint, it likely does not fall under project activities.